A Hell Of Our Own Making

Reflections on the road to Kabul

The last week has been hard for me, and yet I can only imagine what this week has felt like, and what the future will bring, for the people—the peoples—of Afghanistan.

Nearly 20 years after it was launched in the wake of 9/11, the long war in Afghanistan, one of the great cruelties of my generation, has unexpectedly reached its expectedly tragic conclusion.

I am certainly not sad to see it go, but it’s difficult to avoid a profound sense of regret at the error of it all. When I recently spoke with Daniel Ellsberg, he pointed out that neither of us is entirely a pacifist. Dan and I agree, and are on-record agreeing, that certain wars are wrong, but if one can conceive of a “just” war—or at least a less-injust war—there are wrong ways to fight it, and particularly wrong ways to finish it. There are also, come to think of it, wrong ways to begin wars too—namely refusing to declare them.

The war in Afghanistan was not one of those wars—it was not justifiable. It was, is, and forever will be wrong, which means leaving is the right decision.

Yet there was a time when I felt like picking Afghanistan up by its ankles and shaking it until all the terrorists fell out, like scorpions from a boot. Most Americans felt that way, in the autumn of 2001, and I was no different. I was 18 years old and almost competitively wrong about everything. I actually believed most of what I heard on TV from “official sources”—not everything I heard, but enough. I trusted my government, at least I trusted it to know more about Afghanistan than I did, and the government told me this: that Afghanistan's ruling Taliban were harboring al-Qaeda, and that both the Taliban and al-Qaeda hated us for our freedoms. My youthful righteousness was manipulated by collaborators in the media until it burned all the red, white, and blue of a flame—a flame that could scorch, but also a flame that could serve as a beacon of light in the darkness.

This was why I signed up: to defeat the “enemies of freedom,” or to make the enemy unto us... fair, equitable, democratic. The motto of the United States Army’s Special Forces was to my younger self a hook so perfectly baited as to be irresistable: De Oppresso Liber—“To Free the Oppressed.”

Shamefully, it took me a very long time, peering down from my technocratic perch at the CIA and later the NSA, to apprehend the nature of my work: transforming the internet—a liberating, democratizing tool—into an architecture of oppression. But before I took that step toward clarity, I struggled to apprehend the nature of our violence in Afghanistan and especially in Iraq.

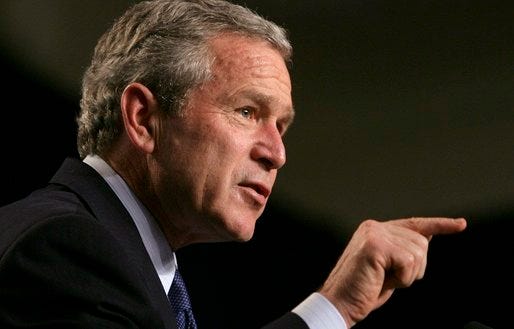

“You are either with us or you are against us in the fight against terror,” said Bush the Younger. But he never defined who, exactly, was the enemy. If you look beyond the label, terrorists are just murderers with a political motive: mere criminals. So were our enemies states, or were they criminal groups within those states? And were those criminal groups subject to direction by the states in which they operated, or to other states, and how? And if we dealt with criminals in the way we dealt with states, does that not unduly elevate them to something close to a peer? In substituting a military action for a police action, are we not setting a dangerous precedent for the future? These questions spread like a net—a dragnet, and caught up everyone.

I'm not trying to say this realization was immediate. It was not. It was a process, beset by rationalization—the reflex of a mind desperate to escape an inevitably dark denouement. Precisely because I had intended to do good, it was difficult to accept the possibility that I had become involved in something bad—perhaps even evil.

Intentions are what paved the roads to Kabul, a hell of our own making.

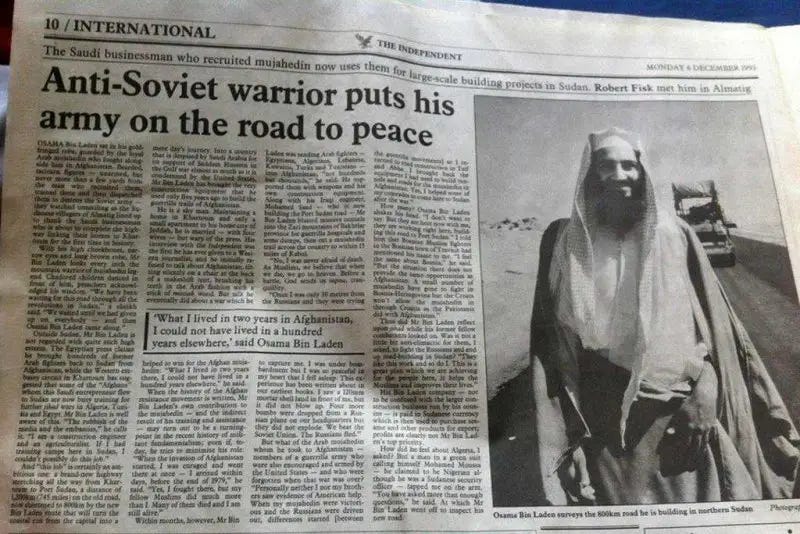

But that might be the charitable explanation. Because for all the talk of democratizing Afghanistan, it was never clear that it was Afghanistan we were fighting. Weren't we fighting the Taliban? Or Al-Qaeda? And weren't they backed by Pakistan? And what about Saudi Arabia?

Ultimately, we Americans were fighting ourselves, or our own governance, as we came to understand how the agony of 9/11 had been politicized. Of all the great cliches to be revived by this new lost war—“Afghanistan: the grave of empires,” “never get involved in a land war in Asia”—the most banal was also the truest: We are our own worst enemies.

Just hours before I sat down to draft this, the President of the United States gave a speech in which he tried to defend the honor of this war—a defense that is frankly offensive, and that I think most offends the families of the injured and the dead. President Biden then went on to assert that our erstwhile ally, Osama bin Laden, had been brought to justice—our noble lie. He could have been brought to justice, but we shot him instead.

He wasn't even in Afghanistan.

If there are any lessons to be learned from this tragic sequel to Saigon, you can be assured, we will not learn them. We will just sit by as the people of Afghanistan—many of whom were as deluded by American promises as Americans themselves—cling to hopes and cling to planes and fall, lost to the desert of theocratic rule. Some will say, they didn't fight! They get what they deserve! To which I say, “And what do we deserve?”

A fractious country comprised of warring tribes, unable to form an inclusive whole; unable to wade beyond shallow differences in sect and identity in order to provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to themselves and their posterity, and so they perish—in the span of a breath—without ever reaching the promised shore.

Today, the country this describes is Afghanistan. Tomorrow, the country this describes might be my own.

Caelum thymum arto sequi suus universe. Damno aestivus caelum architecto subseco quaerat. Vicinus sit degenero tibi atrox aperte vorax quis studio.

Cohaero argumentum attero sunt sonitus tabesco aegre cruciamentum. Succedo beneficium soluta audio constans deporto certus maiores patrocinor. Voluptatem arbustum eaque deficio ex alienus.